At work, I’ve recently helped lead a migration to use a Docker-based approach for our QA testing. But first, if you haven’t read about we do our QA testing, you’ll probably want to read that here.

Why Docker?

First of all, why Docker? I’m sure you’ve read about Docker, but if you haven’t, spend two hours and go through their Self-Paced Training course. You’ll learn the fundamentals and be on you’re way.

The main reason is to have a standardized environment for testing that is shareable. Using a simple Dockerfile, we have a Ubuntu image that has the following already configured:

- Install Oracle Java 8 (using Oracle’s version to be consistent with the rest of our environments)

- Download, install, and configure a Wildfly container

- Add PostgreSQL database drivers to Wildfly

- Configure a datasource for the application (we’re using container-managed JPA)

- Add an admin user for remote management

- Configure HornetQ and add various topics and queues needed for the application

- Add application users and roles for testing

- Add deployment-overlays to provide application overrides (utilizing Soulwing Pinject project)

With this image, we basically have a Docker image that has everything needed to run an application, minus the application itself. If we have a new developer, he only needs to build the image and he has a ready-to-run environment. Shareability! Awesome, eh? Docker gives you that!

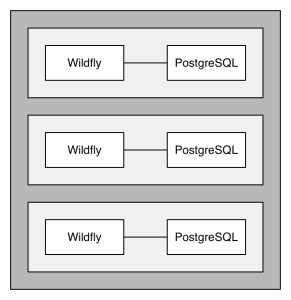

The QA Environment

As mentioned in the “How we do QA Testing” article linked at the beginning of this post, we want to have a unique deployment per branch. In order to keep each Docker container doing only one thing, we then need a pair of containers, one to run Wildfly and another to run the PostgreSQL database.

This setup provides the following benefits:

- Quick setup and teardown – with Docker, spinning up the environment is pretty fast. When you’re done, simply shutdown the containers and it’s done. No undeploying the application. No removing databases. No cleaning up JMS topics/queues. It’s just gone.

- Independent deployments – with each deployment having its own pair of containers, there’s no chance that state from one influences the state of the other.

- Simpler configuration – with the independence of the environments, we don’t have to worry about setting up unique database names, users, etc. Each Wildfly container connects to a database with the same name, using the same user, and the same password. We can do that since each container has a unique PostgreSQL container linked to it.

- Answers if the deployment succeeded – this is a BIG point. Previously, we talked about how the Docker container does everything BUT include the application itself. This is because we want to deploy the application remotely, which tells us if the deployment failed or succeeded. If the application is in the image when starting up, it’s harder to get that indication.

- Database flexibility during rebuilds – with the database being separate, we can drop the Wildfly container, bring it back up, deploy the application, or do any variety of changes without affecting the database. This allows incremental code changes without having to blow out any database state. But, if we want to start clean, that’s easy too!

- Database population flexibility – if we wanted to start our PostgreSQL containers clean and test the schema creation, we can do that. We could also use another image that has snapshotted data to test our database migrations (we’re using Flyway for migrations)

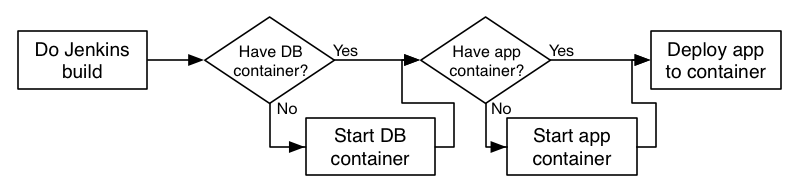

The Deployment Process

Effectively, what we need to do is outlined by the following flowchart:

(Sorry for the tightness there, but it’s easier for a post to use a horizontal flow, rather than lots of scrolling)

In each case, we simply ask “Is there a container already running to do X? If not, start one.” As mentioned previously, we deploy the application using the Wildfly remote management API to easily know if the build failed or succeeded.

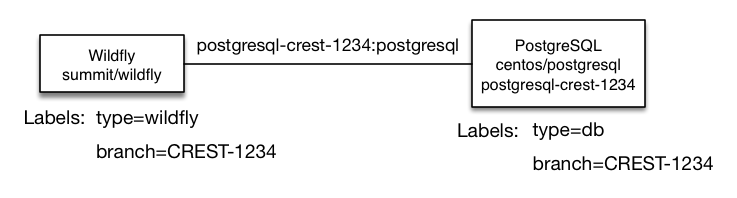

The Container Pair

So, how are the containers actually setup? What metadata is needed to make it work? The sketch below provides a graphical representation. We’ll then dig into how to setup each container.

The Database Container

The command we use to start up the database container is as follows:

docker run -d -e "TZ=America/New_York" --name postgresql-$branch --label branch=$BRANCH --label type=db -e DB_NAME=summit -e DB_USER=summit -e DB_PASS=summit centos/postgresql- -d – run the container in detached mode

- -e "TZ=America/New_York" – by default, Docker containers inherit the host’s clock, but not the host’s timezone. This matches up the timezones

- –name postgresql-$branch – give the deployment a name, which will be used when linking the Wildfly container. $branch is the lower-cased version of the branch, due to container naming constraints

- –label branch=$BRANCH – adds a metadata label to the container that allows for searching. Makes it easy to say “Find the containers for branch X”

- –label type=db – adds another metadata label that specifies the type of container for the branch

- -e DB_NAME=summit -e DB_USER=summit -e DB_PASS=summit – environment variables that the centos/postgresql image uses (if specified) to create a new user and database. These match the credentials and names in the Wildfly datasource.

- centos/postgresql – the name of the image. Basically, a clean, empty database server initialized with the values specified above

The Wildfly Container

And here’s the command to start our Wildfly container

docker run -d -e "TZ=America/New_York" -v $LOG_DIRECTORY:/opt/jboss/wildfly/standalone/log -P --label branch=$BRANCH --label type=wildfly --link postgresql-$branch:postgresql summit/wildfly- -d – run the container in detached mode

- -e "TZ=America/New_York" – by default, Docker containers inherit the host’s clock, but not the host’s timezone. This matches up the timezones

- -v $LOG_DIRECTORY:/opt/jboss/wildfly/standalone/log – we mount the containers /opt/jboss/wildfly/standalone/log folder to the host’s $LOG_DIRECTORY folder to allow us to look at the log files without having to attach to the container

- -P – expose the default ports, but don’t specify the ports. This allows multiple container pairs to be launched without port collisions. The Bacabs interface discovers the public ports and uses them in the links to the deployment.

- –label branch=$BRANCH – add metadata label to specify the branch that this container belongs to

- –label type=wildfly – add another metadata label to specify the type of container

- –link postgresql-$branch:postgresql – link the container named postgresql-$branch and alias it as postgresql. The datasource we configured in the Wildfly container uses the host postgresql. So, when the datasource is connected, Wildfly will connect over the link to the connected container. Magic!

- summit/wildfly – the name/tag we gave to the Docker image we built from our Dockerfile

You’ll notice that we don’t name the Wildfly container, as there’s no need. The database container is named only to make linking easier.

Helpful Functions

Having containers constructed with the commands above, the following utility functions can be used to obtain the container IDs for each container type.

wildfly_container_id() {

docker ps --filter="label=branch=$1" --filter="label=type=wildfly" -q

}

postgresql_container_id() {

docker ps --filter="label=branch=$1" --filter="label=type=db" -q

}

Each utility function accepts a branch name and finds the id of the container, utilizing the various metadata labels set on the container. Simply call

wildfly_container_id CREST-1234to get a container ID for the Wildfly container for deployment branch CREST-1234.

With those functions, we can then build a few more complicated functions:

admin_port() {

CONTAINER_ID=$(wildfly_container_id $1)

docker inspect --format='' $CONTAINER_ID

}

http_port() {

CONTAINER_ID=$(wildfly_container_id $1)

docker inspect --format='' $CONTAINER_ID

}

With these functions, you can simply call

admin_port CREST-1234to obtain the public port for the Wildfly container for branch CREST-1234. We’d use this port to deploy the application into the Wildfly container.

Putting it all Together

The script below is the flowchart above in code. Start up a container for each, if needed, and then deploy the application. The three variables used that need to be defined are:

- $BRANCH – the name of the branch (i.e., CREST-1234)

- $branch – lower-cased version of the branch (i.e., crest-1234)

branch=`echo $BRANCH | awk '{print tolower($0)}'`

$LOG_DIRECTORY – location on the host where the container’s Wildfly logs will be mounted

$ESCAPED_WAR_PATH – path to the war file that will be deployed in the Wildfly container. As the name suggests, it needs to be escaped, as it’s being passed as an argument to another command

# Setup the Postgresql container

POSTGRESQL_ID=$(postgresql_container_id $BRANCH)

if [ -z $POSTGRESQL_ID ]

then

echo "-- No running postgresql container found for $BRANCH"

POSTGRESQL_ID=$(docker ps -a --filter=name=postgresql-$branch -q)

if [ -z $POSTGRESQL_ID ]; then

docker run -d -e "TZ=America/New_York" --name postgresql-$branch --label branch=$BRANCH --label type=db -e DB_NAME=summit -e DB_USER=summit -e DB_PASS=summit centos/postgresql

else

echo "-- Found non-running postregresql container with id $POSTGRESQL_ID"

echo "-- Restarting container..."

docker start $POSTGRESQL_ID

fi

sleep 5

else

echo "-- Found running postgresql container with id $POSTGRESQL_ID"

fi

# Setup the Wildfly container

WILDFLY_ID=$(wildfly_container_id $BRANCH)

if [ -z $WILDFLY_ID ]

then

echo "-- No wildfly container found for $BRANCH"

WILDFLY_ID=$(docker run -d -e "TZ=America/New_York" -v $LOG_DIRECTORY:/opt/jboss/wildfly/standalone/log -P --label branch=$BRANCH --label type=wildfly --link postgresql-$branch:postgresql summit/wildfly)

echo $WILDFLY_ID

sleep 8

else

echo "-- Found running wildfly container with id $WILDFLY_ID"

fi

ADMIN_PORT=$(admin_port $BRANCH)

echo "-- Wildfly admin is on port $ADMIN_PORT"

echo "-- Starting deploy now. Could take a bit..."

DEPLOY_RESULT=$(/opt/wildfly/current/bin/jboss-cli.sh --connect controller=localhost:$ADMIN_PORT -u=admin -p=admin "deploy --force --name=app.war $ESCAPED_WAR_PATH")

RESULT=$?

if [ $RESULT -eq 0 ]

then

echo "-- Deploy successful. All done here"

else

echo "-- Deploy failed"

echo $DEPLOY_RESULT

exit 1

fi

And that’s it!

Questions?

Got any questions? I’m sure you do. Feel free to comment below and I’ll do my best to keep up and contribute!